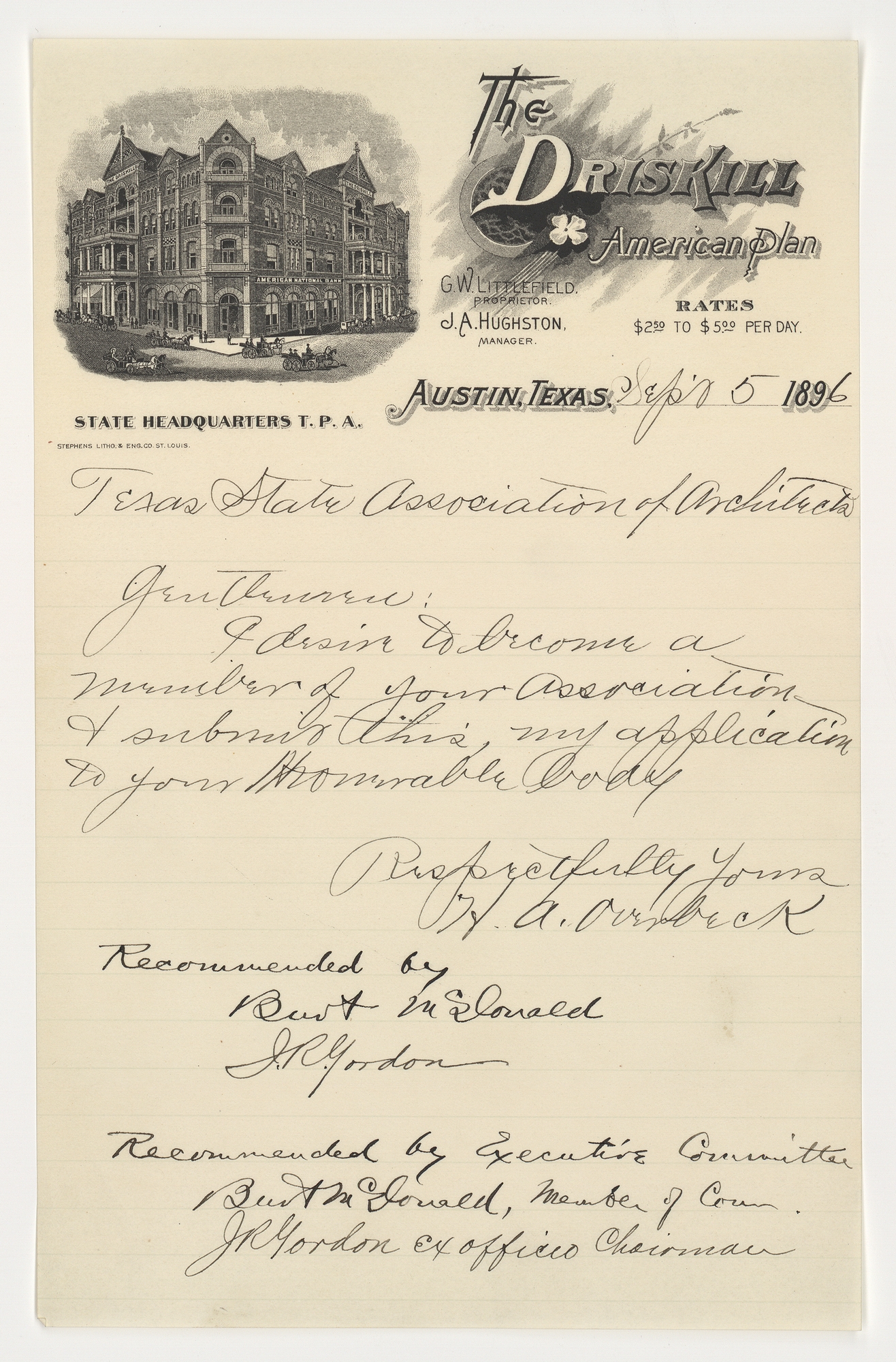

Texas State Association of Architects

Texas State Association of Architects records from the James Riely Gordon collection and the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company collection at the Alexander Architectural Archives. A document from the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company collection, the Texas State Association of Architects Year Book 1917,...

Project by Katie Pierce Meyer